Everytime you venture into the backcountry, there is a point where your swollen shoulders and tired legs beg the question, “Did I pack too much?”

In this edition of Therm-a-Rest Gearshed, contributor Dan Hilden helps adventurers figure out where and when light is right.

The trail climbs out of sight into the misty world of green and grey, ancient Douglas firs blocking most of the light of the overcast fall day. I try to focus on putting one foot in front of the other and do my best to avoid dwelling on the thoughts that keep popping into my mind. The trail parallels the lake, so why are we going uphill right now? Why am I so tired after only a few miles? How far did we say we would hike today? The shoulder straps of my massive new pack dig into my flesh and its weight bears down on my spine as I lean forward to shift the load. Finally, I reach the top of the hill and find my friends slumped against their burdens, as soaked with sweat as I am.

We descend the hill and wind around the inlets and patches of devil’s club along the shore of the lake until we find a patch of clear dirt among the six foot in diameter trees and thick carpets of moss. I unsnap the waist belt from my chaffed hips and let my pack fall to the ground. I unclip my camp stool from the outside of the pack and pull out a two-liter bladder of water, filled to the brim. My friends get to work on setting up each of their three-person tents. There must be a better way, I think to myself, as I begin to dig through my pack for my own tent.

A few years later, I find myself shivering violently high in the North Cascades. It’s the middle of the summer, but our tarp shelter does little to hold back the stiff breeze blowing cold air down from the glacier above. My minimal insulation consists of a lightly insulated jacket and the torn reflective fabric of my lightweight bivy sack. Nestled inside an ultralight down sleeping bag my climbing partner, Blake, snores as I begin to do push-ups and sit-ups in an attempt to stop my teeth from chattering.

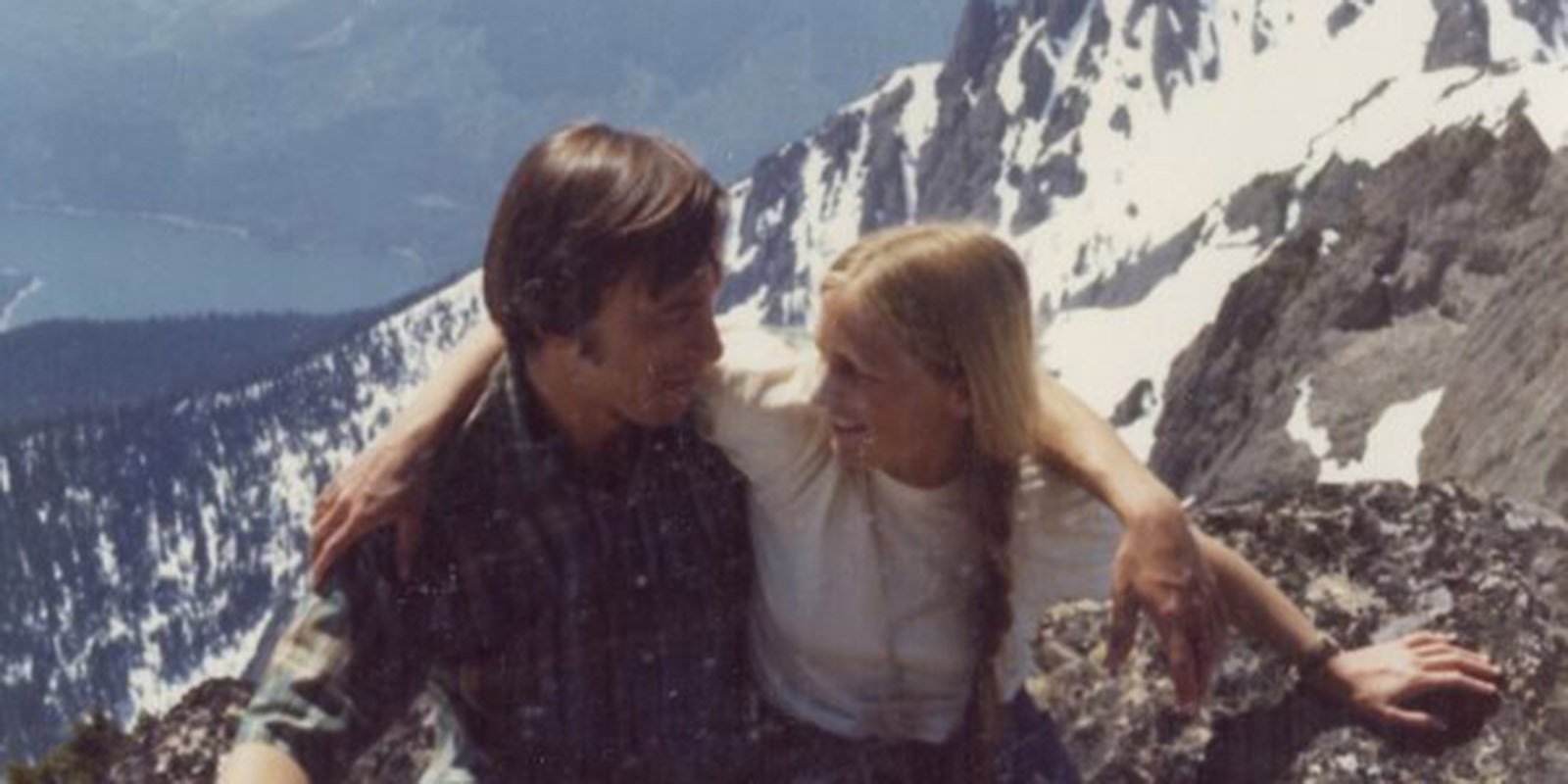

It was 2007, and Blake Herrington and I were attempting a rambling high-country traverse of the North Cascades; a journey we expected to take two weeks. Since my heavily laden early backpacking trips, I’d evolved into a fast and light aficionado: I carried no sleeping bag, a silly ¼ inch thick pad, and minimal food. Below treeline I managed to get some sleep each night, but at higher elevations, I found that the shivering kept me up. After a couple of sleepless nights, my body was unable to properly recover from the work of hiking and scrambling. I could no longer move fast, despite my light pack. Halfway through our trip, we were driven out of the mountains by heavy rain and I never had to admit that my strategy had been self-defeating.

There is a fine line between bringing too much and not bringing enough when going into the backcountry. Bring too much, and every step can feel like misery. Bring too little, and what should be a restful night will be something dreaded rather than savored. I know both feelings well, but after hundreds of nights spent out in the mountains over the last 15 years, I’ve got a feel for what I need, what I like to have, and what I will never carry again. I’ll be covering just the essentials for multi-day trips. You might be adding climbing, skiing, fishing, hunting, or photography equipment to your pack, which is just another reason to try to lighten up your overall load.

Sleeping Pads

As someone who spends time in the mountains year-round, I like to have options when it comes to pads. Just 10 or 15 years ago there was a huge weight difference between warm, comfortable pads and lightweight, less comfortable ones. These days, there’s little need to sacrifice comfort for weight. In the last couple of years, I’ve used a NeoAir XTherm about 90% of the time. It’s light (20 ounces for the size large), warm enough to use in any conditions, and long enough so that I can stretch out my 6-foot frame without hanging off the ends. The NeoAir XLite weighs only 12 ounces, making it an even better option than the XTherm for three-season use.

Sleeping Bags and Quilts

I tend to sleep warm and am usually willing to sacrifice a little warmth to save weight. How light is too light, considering that the goal is to get the rest your body needs to recover for the next day? That varies from person to person and will take a little trial and error to figure out. During summer in the Cascades, I use a down quilt. Quilts take some getting used to, but when combined with a good pad the warmth to weight ratio is hard to beat for the price. On particularly cold nights, I’ll sleep with all my insulating layers on, including a wool beanie and a pair of dry socks.

In the winter and spring in the Cascades temperatures rarely drop below 10°, so I’ll use a 20° bag and wear all my layers, including a big puffy jacket if I’m expecting temperatures below 20°. Another option is to fill a sturdy water bottle or bladder with hot water, wrap it in a shirt or jacket to avoid direct contact, and sleep with it in between your thighs so that it warms the blood flowing throughout the lower half of your body. If you tend to get cold at night or live in a colder climate like the Rockies, consider going for a 0° bag for the winter, and a quilt for the summer. That way, if you’re going out on a brutally cold winter night that will test the limits of your bag, you can spread the quilt over your bag. One thing to keep in mind for winter camping is that if your pad doesn’t have enough insulation, your bag will struggle to keep you warm no matter what its temperature rating is.

Protection from the Elements

The last part of your sleep system is the shelter. You can shave a lot of weight here if you’re flexible. In the summer, I’ll usually just bring an ultralight sil-nylon tarp that I can string out if the weather turns. Sometimes, I might also bring a mosquito net that I can rig up with trekking poles or string. If I know that bugs will be more of a problem than rain, I might bring a tent without a rainfly. Conversely, many tents can be set up with just the poles and rainfly if you’re more worried about weather than bugs. While snow camping I’ll sometimes bring a pyramid-shaped floorless tent. They’re spacious, lighter than a full-on tent, and offer suitable protection against showers and light wind. If I expect to sit out a storm or will be out for so long that I can’t accurately predict the weather, I’ll bring a real tent. There are plenty of good, light tents on the market these days; if you can share the weight with a tentmate you shouldn’t need to carry more than a couple of pounds.

One thing to remember if you’re not bringing a tent is to bring a groundsheet to protect your inflatable sleeping pad from things like sharp rocks and pine needles. A piece of house wrap left over from a construction site or the footprint from a tent works great. If you bring something oversized, you can fold it over your sleeping bag if the weather turns. You’ll get damp with condensation, but it’s better than nothing.

Trail Fashion

I’ve got good news: no one who you run into in the mountains will care that you’ve been wearing the same shirt and pants for 3, or even 10 days. Usually in the summer I’ll bring a wicking tee shirt, quick-drying pants, a thin long sleeve shirt (to protect against sun, wind, and bugs), a lightly insulated jacket, a wool hat, and some kind of shell; either a minimalist, water-resistant wind shirt, or a full-on rain jacket. That’s all, no matter how long the trip is. In the fall and spring, I’ll add long underwear, rain pants (for dewy mornings as much as rainy days), and maybe a heavier puffy. In the winter I’ll usually have sturdier shells, and maybe insulated pants for wearing around camp and sleeping in. As far as socks go, I’ll bring only one or two extra pairs and dry damp pairs against my body during the night.

There’s an old adage that that one pound on your foot is equal to five pounds on your back when it comes to expending energy, and studies have shown that to be fairly accurate. Considering that a pair of traditional hiking boots weighs half a pound to a pound more than hiking or trail running shoes, you might be able to save a lot of energy by using lighter footwear. I wear trail shoes unless I’m carrying a really heavy pack or expect to cross a lot of snow. Know your body: if you’ve been relying on high topped boots for years, transition to hiking in shoes slowly in order to build up lower leg muscles.

Think Multipurpose

Duct tape can cover blisters, repair gear, and patch holes in your clothes. Carry a few feet of it wrapped around a trekking pole or pencil. Traditionalists might roll their eyes when they see someone pull out a cell phone in the backcountry, but modern phones can serve as a camera, GPS, music player, a place to save route descriptions or maps, and even a communication tool in many mountainous areas. It might be worth bringing an extra battery or spare power pack if you’re going to be out for a while. It’s always a good idea to bring paper maps, but I’ll usually bring small printed copies of just the areas I need and rely on my phone as my primary navigation tool.

When you have some spare time, load up your pack with everything you would bring on a two-night trip. Then think everything over as you unpack it, keeping in mind that ounces quickly add up to pounds. What could be made lighter? What can you share? Many one-liter water bottles marketed to outdoor enthusiasts weigh more than six ounces. A leftover sugary sports drink bottle weighs less than two ounces. A headlamp is essential, but you can probably get by with a very small one. A half-full can of isobutane stove fuel should be plenty for two people for two or three days in the summer. One person can carry the fuel and stove, the other can carry the pot. A knife is worth having for many reasons, but the reality is that you probably only need one that’s big enough to slice cheese, and maybe chop a clove of garlic.

In the end, remember that there are no rules. Sometimes I bring an inflatable pillow, sometimes a book, and other times I might bring a few cans of IPA. Oftentimes a pair of flip-flops to wear around camp is absolutely worth the weight. Bring what you think you’ll need to get the most out of the experience, and eventually, experience will tell you what you don’t need. Be mindful as you pack, and over time you’ll find yourself leaving unnecessary items behind. There’ll be days when your pack feels way too heavy for the hills that you’re slogging up, and nights when you’ll wish that you carried more. Embrace those times; they might make for good stories someday.